Barnacles are some of the coolest animals around. They are arthropods – so related to crabs and insects and spiders and shrimps – but the untrained eye might be confused by the shell that surrounds them, which is made up of a number of calcareous plates. The best-known claim to fame of barnacles is that, relative to body size, they have the largest penis in the animal kingdom! Barnacles live in all sorts of places: on rocks (acorn barnacles), on floating marine debris (goose barnacles), and even on whales (whale barnacles).

From left to right: acorn barnacles, goose barnacles growing on a bottle, whale barnacles.

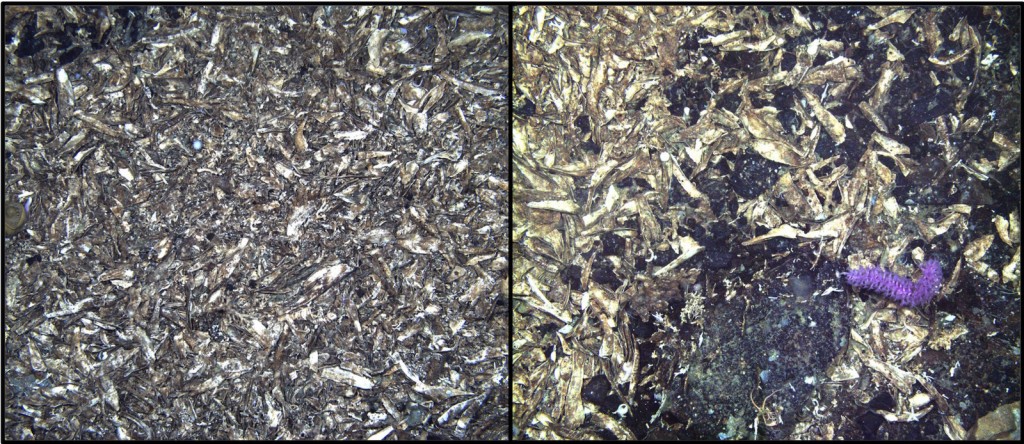

Today, we were investigating the sea floor at around 1000 m depth, south of the South Orkney Islands, Antarctica. When we first put the camera down on the sea floor, the strangest site greeted us. The seafloor was a mass of shell debris. But shells of what? The fragments were not the right shape to be the shells of clams. It certainly wasn’t coral debris, which can also look chalky white. Have a look at the drop down camera images to see what we saw. You may have guessed from the title of this post that they were barnacle shells or, more accurately, individual plates from barnacle shells.

Photographs from the underwater camera system showing two areas, each 50 cm x 50 cm, containing large numbers of fossilized barnacle plates. Note the purple octocoral Bayergorgia in the right hand photo. Photos taken from RRS James Clark Ross, courtesy of British Antarctic Survey.

I’ve never taken images like that before, but I have seen them. The US ship Okeanos Explorer live streams video from its ROVs (remotely operated vehicles), and Okeanos Explorer found a barnacle graveyard off Hawaii in August 2015. After much searching, the Okeanos team also found live barnacles…

Left: fossilized barnacle plates, a ‘barnacle graveyard’, found in deep water off Hawaii by Okeanos Explorer. Right: a live barnacle in the same area. Photos from Chris Mah’s Echinoblog (echinoblog.blogspot.com), originally from live streamed Okeanos Explorer footage.

We didn’t find any live barnacles. We did however subsequently tow one of our small gears through the site to see if we could collect any shells to verify our identification. Nearly all the shells that we pulled up were fossilized. We don’t know how old they are (although one of our team will do some radioisotope dating when we get back) but we appeared to collect a range of ages. The very youngest (which look clean and white as in living animals) were scarce, suggesting perhaps that there are not the huge quantities of living barnacles in the area as suggested by the huge amount of shell debris, but rather that barnacles have been growing (and dying) in this area for a very very long time.

Fossilized and recent barnacle plates. Most of the plates we encountered were covered in Manganese (hence dark) – a sure sign of having been on the sea floor a long time. Just a very few were new and white as in the top left.