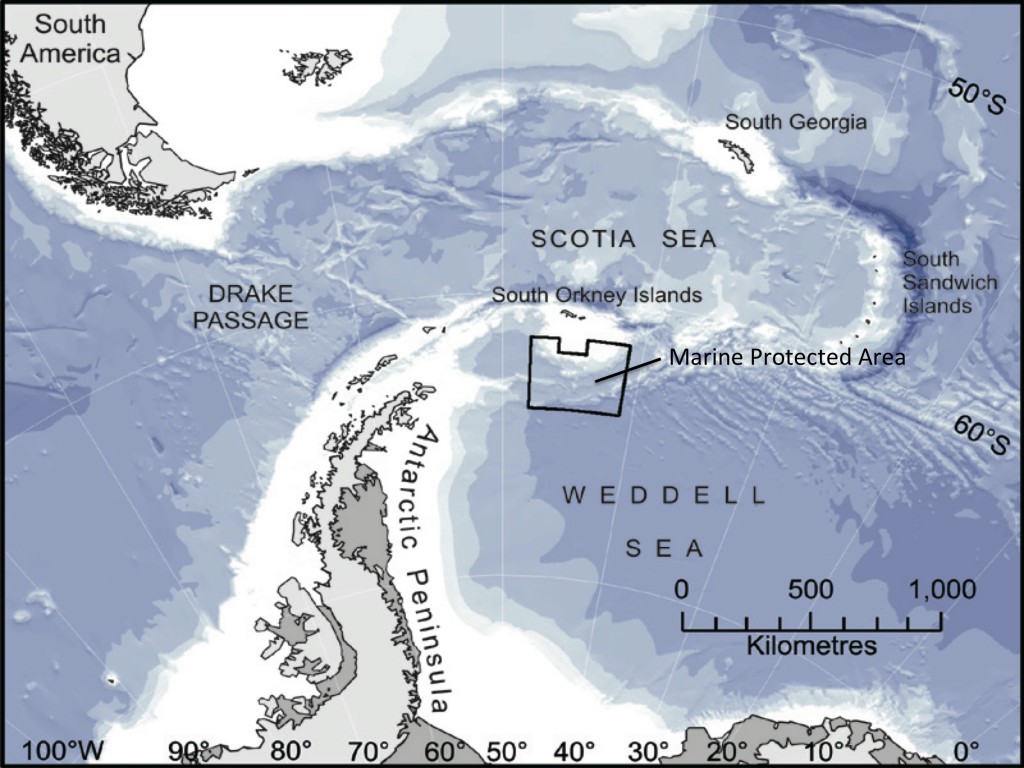

I am in the Antarctic! I’m here, aboard the James Clark Ross, surveying a Marine Protected Area which, in 2009, was the first in the world to be established entirely within the High Seas.

British Antarctic Survey research vessel RRS James Clark Ross off Signy Island, South Orkneys, Antarctica, 29th February 2016.

Most Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) tend to be close to the coast. There are several reasons for this. For example, because coastal areas are better known, we know where rare habitats and species exist, so it is easy to designate protection. There has also been a long-standing perception that, in contrast to shallow coastal waters, the deep sea is all the same and that there is so much of it that it doesn’t need protecting. We increasingly know this perception is wrong. The deep sea is highly variable and parts are rich in highly sensitive habitats – so called Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems – and it is essential that these are given some protection. In Irish waters, the National Parks and Wildlife Service keeps a database of cold-water coral records and has designated several offshore areas to protect deep-water corals.

A black coral (right), so called because of its black stem, and two octocorals (top and bottom left) found about a mile deep in Irish waters.

But international marine legislation is wildly complex, and designation of protected areas in ‘Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction’ (i.e., offshore waters that don’t belong to any one country) is incredibly difficult and requires complex negotiations among all nations that wish to exploit those waters. It may not surprise you to learn that the MPA we are surveying is the only MPA in Antarctic waters. To date, attempts to designate other areas have failed because of nations looking to protect their fishing interests. The designation of this one probably succeeded because it doesn’t cover favoured fishing grounds. In fact, the ‘notch’ in the otherwise square shape, was to facilitate a Russian exploratory fishery for crabs.

The location of the 94,000 km2 MPA was based on surface ocean characteristics and encompasses critical penguin feeding areas on the southern boundary of a krill fishing area. The MPA prevents the krill fishery expanding southwards, ensuring that plenty will be left for the penguins and other predators. It also protects vulnerable benthic habitats from the potential impacts of exploratory toothfish fisheries. Toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) are fished using long lines about 1000 m deep. Long-lining involves dropping bated hooks to the sea floor and these hooks can be massively destructive to deep-water corals and other habitat forming animals such as sponges. Because the MPA was located based on surface ocean characteristics, it’s not at all clear what the sea floor habitat is like. That’s where we come in. Over the next few weeks we will be surveying the sea floor inside and outside the MPA from the British Antarctic Survey research vessel RRS James Clark Ross. What we find may confirm that the MPA is perfectly positioned to protect seafloor habitats, or our data may suggest expansion of the MPA is required.

Internet connectivity permitting, I’ll be blogging more about my exploits in Antarctica over the coming days.